|

With the passage of a new Fugitive Slave Act looming in late 1850, John Carson McAllister eyed an opportunity that seemed tailor-made for his son. The new bill making its way through Congress encouraged Federal courts to hire additional commissioners, who under the new law would be empowered to hold hearings in any cases involving runaways, and act as the sole adjudicator in the matter. He wrote to Supreme Court Justice Robert Grier (Class of 1812), recommending his son Richard be appointed a commissioner for Dauphin County. As a result, on September 30, 1850—just twelve days after the new Fugitive Slave bill had become law—Chief Justice Roger Taney (Class of 1795) signed McAllister’s appointment as U.S. Commissioner.

The very same day as his appointment, September 30, McAllister heard his first case involving fugitives, two men named Samuel Wilson and George Brocks. [2] McAllister’s brand of justice was swift and severe, just what slaveholders. Historian Richard Blackett notes that McAllister appears to have not required even “the most summary evidence," and likely possessed no “irrefutable proof” that Wilson and Brocks were indeed slaves. Going a step further, McAllister sought to prevent any interference from Harrisburg’s African-American community, commissioning an armed pose of some twenty-odd men to convey the two fugitives back to Virginia, at the considerable expense of $263.91.[3] |

"I feel it my duty as a U.S. Commissioner and a friend of Southern rights..." |

resistance

"More fugitives have been remanded by me than any other U.S. Com." |

Harrisburg attorney Charles Rawn, an anti-slavery Democrat, had been monitoring the case of Wilson and Brocks for some time. He was shocked to learn that Taylor had brought the fugitives before McAllister, where “his own oath and that of only one other Witness” was enough to send the two men back to slavery. “The law is an abomination and the hearing a farce,” he penned angrily in his diary. [4]

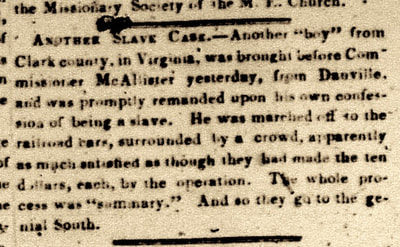

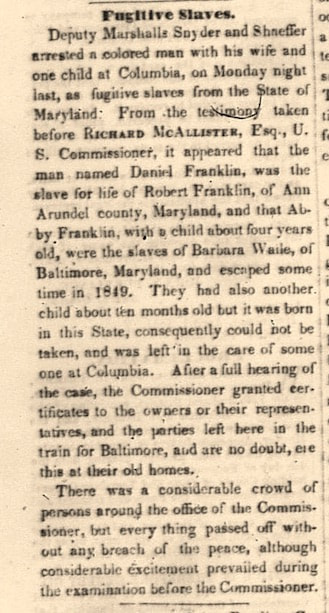

The "abominations" had only begun. In April 1851, McAllister separated the Franklin family, returning a father, mother and oldest child to bondage in Maryland, while their newborn infant remained behind, having been born free on Pennsylvania soil. In August 1851, his deputies arrested Bob Sterling, the slave of a Maryland woman. Despite “a number of negroes [who] collected at and near the Commissioners [sic] office” in protest, McAllister held a customarily prompt hearing and ordered Sterling be returned to slavery. [5] In October 1851, McAllister was accused of colluding with slaveholders and personally profiting from renditions. [6] While McAllister was successful, he did not go unopposed. Rawn was joined by Mordecai McKinney, another anti-slavery lawyer and member of the Class of 1814. They were up against a hostile environment and a difficult commissioner. Unlike a normal courtroom, “no accommodation whatever, in pens, paper, or table” was provided for Rawn or McKinney, and the two lawyers “were obliged to take notes, if any, on their hats, hands, or otherwise[.]” McAllister reportedly “restrained” Rawn and McKinney from conducting “a fair and full cross-examination” of alleged fugitives, and showed “the most marked dissatisfaction and uneasiness” that the two lawyers were present at all. [7] |

"Excessive zeal"In the face of criticism, McAllister doubled down. “More fugitives have been remanded by me than any other U.S. Com.,” he proudly wrote Treasury officials in Washington. He argued that his tactics were “much better for the peace and interest of the country,” preventing violence against “claimants and the U.S. officers” involved in recaption (a clear reference to the Christiana incident). [8]

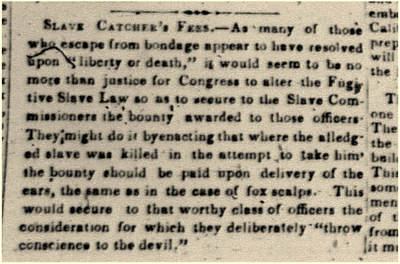

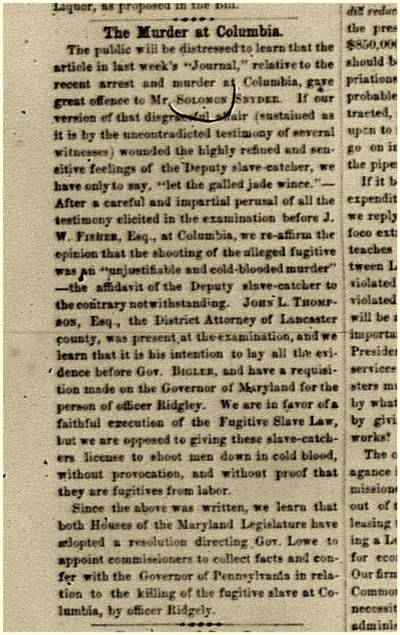

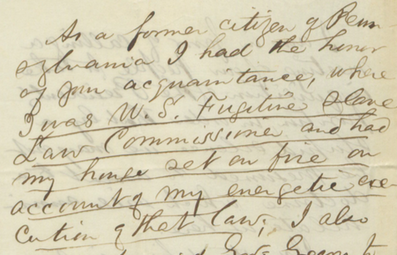

His troubles were compounded when in May 1852, a Baltimore slave catcher—bearing a warrant from McAllister—gunned down an alleged fugitive in Columbia. [9] The previously supportive Telegraph cried out with the headline: “MURDER UNDER THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW.” [10] McAllister's deputies, the paper sneered, should “be paid upon delivery of the ears, the same as in the case of fox scalps.” Far from their earlier defense of McAllister, they now declared that he and his deputies “deliberately ‘throw conscience to the devil’” in violently pursuing “alleged” fugitives for monetary gain. [11] “We are in favor of a faithful execution of the Fugitive Slave Law,” read a May 1852 issue of the Whig State Journal, “but we are opposed to giving these slave-catchers license to shoot men down in cold blood[.]” [12] Another paper claimed that McAllister’s “excessive zeal” had rendered the law “odious[.]” [13] In July 1852, McAllister’s home was set on fire and badly damaged. [14] By then, even the “indefatigable Commissioner” realized that he had lost the war for public opinion in his hometown. [15] "my house [was] set on fire on account of my energetic execution of that law" - Richard McAllister, 1857[22] His future in Harrisburg quashed, McAllister sought to reinvent himself elsewhere. Relying on his reputation as “a sound national Democrat” who “has done much for the good faith of Penn’a in support of the Compromises,” his friends urged his nomination as territorial governor of Minnesota. Given the press he had generated, McAllister needed no introduction. Courting the incoming Pierce administration in February 1853, one ally simply referred to him as “the famous U.S. Commissioner in this State[.]”[16]

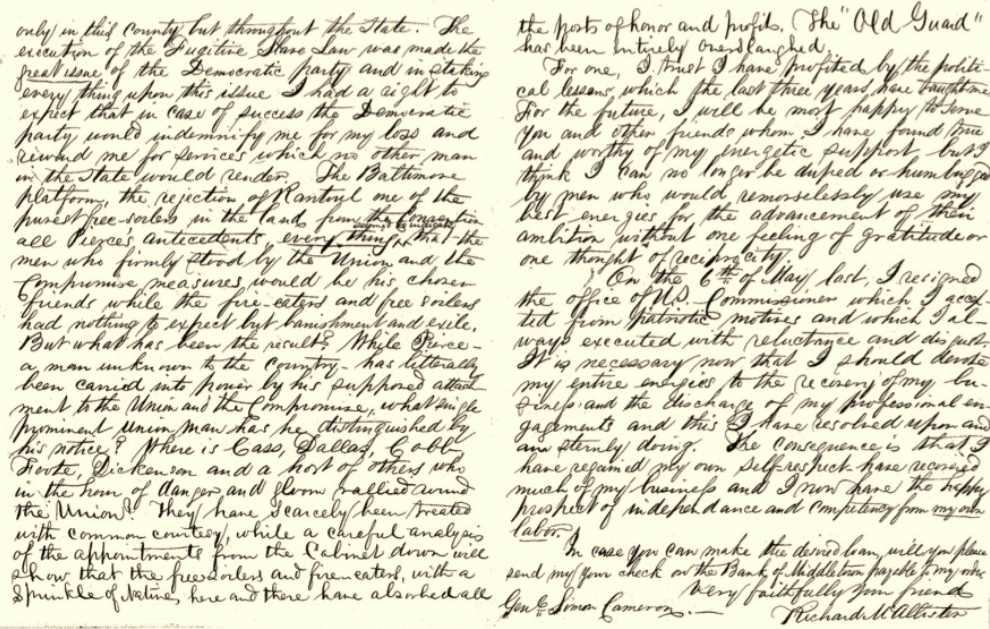

McAllister journeyed to Washington, where he expected Democrats to "indemnify me for my loss and reward me for services which no other man in the state would render." Instead, he left Washington bitter and empty-handed, and his resignation ultimately came in May 1853. [17] For more on McAllister's later life, click here. |

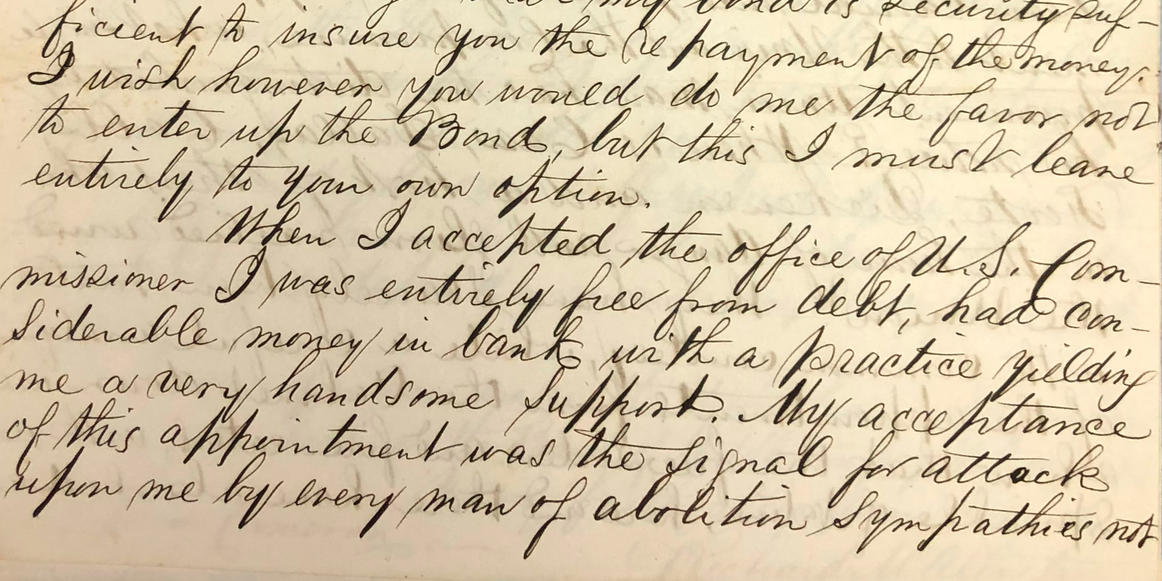

A detail from McAllister's letter to Cameron. McAllister asserts that when he "accepted the office of U.S. Commissioner" he "was entirely free from debt[.]" His "acceptance" was "the signal for attack upon me by every man of abolition sympathies." (Cameron Family Papers, Historical Society of Dauphin County).

McAllister writes to Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois in 1857, touting his credentials as a former fugitive slave commissioner. He wore the attempted arson on his home as a badge of honor to prove his opposition to abolition and his loyalty to the Democratic party. (Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library).

|

Conclusions |

"no decent man in Harrisburg will accept the place" |

What can we learn from McAllister's rapid rise and fall? He was well aware of the stigma attached to remanding fugitives, yet he remained in office until it was clear the Democratic party would not "reward" him for his "services" as commissioner. What does it say that a well-born and well-educated lawyer, from one of Harrisburg's oldest families, felt that he was entitled to a "reward" for depriving 18 men, women and children of their liberty? [18]

A recently-unearthed collection of McAllister's correspondence offers fresh insight into the nation's most prolific fugitive slave commissioner. Admitting defeat, he revealed a pragmatic side. "I trust I have profited by the political lessons," he wrote Cameron, "which the last three years have taught me." Going forward, McAllister vowed to "no longer be duped or humbugged by men who would remorselessly use my best energies for the advancement of their ambition without one feeling of gratitude or one thought of reciprocity." McAllister was, in his own mind's eye, a relentless, self-made man, content to serve any cause he felt would reward him adequately. Once it became clear that the Democrats would not "indemnify" him for his services as commissioner, he was willing to forsake his years of remanding fugitives and turn to other means. Above all, however, he was a man immensely proud of "my own labor" - a phrase he underlined - even if that meant depriving others of their liberty. [19]

A recently-unearthed collection of McAllister's correspondence offers fresh insight into the nation's most prolific fugitive slave commissioner. Admitting defeat, he revealed a pragmatic side. "I trust I have profited by the political lessons," he wrote Cameron, "which the last three years have taught me." Going forward, McAllister vowed to "no longer be duped or humbugged by men who would remorselessly use my best energies for the advancement of their ambition without one feeling of gratitude or one thought of reciprocity." McAllister was, in his own mind's eye, a relentless, self-made man, content to serve any cause he felt would reward him adequately. Once it became clear that the Democrats would not "indemnify" him for his services as commissioner, he was willing to forsake his years of remanding fugitives and turn to other means. Above all, however, he was a man immensely proud of "my own labor" - a phrase he underlined - even if that meant depriving others of their liberty. [19]

"The fugitive slave law is a dead letter" |

Following his resignation, enforcement of the law in Harrisburg dropped dramatically. McAllister was never replaced, because—in the view of one local paper—“no decent man in Harrisburg will accept the place.” [20]

“The Underground Railroad has been doing a heavy business during the past week,” the Harrisburg Morning Herald noted whimsically in June 1854. “After their arrival in this place, the fugitives become invisible…. Nobody ‘knows nothing’ about their whereabouts. The fugitive slave law is a dead letter.” [21] This bold declaration from the Morning Herald would never have been made during Richard McAllister’s tenure. However, absent an individual willing to scorn public opinion to remand slaves, the law was indeed a dead letter. |

The effect of "excessive zeal"

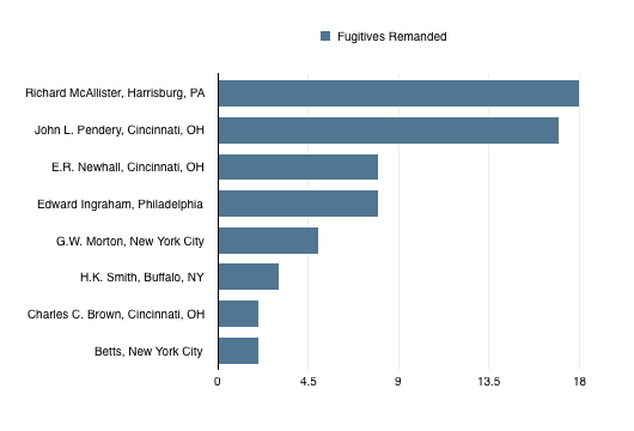

Commissioners responsible for remanding fugitives by Federal tribunals, 1850-1860. Data compiled by Cooper Wingert.

Commissioners responsible for remanding fugitives by Federal tribunals, 1850-1860. Data compiled by Cooper Wingert.

McAllister's "excessive zeal" (or as he termed it in his letter to Douglas, "energetic execution") played a crucial role in his downfall. Historian Richard Blackett has argued that McAllister and other commissioners responded to resistance from African-American communities and abolitionist lawyers by employing "increasingly draconian methods." Armed posses and predawn hearings exemplify what McAllister resorted to in order to enforce the law. Consequently, the law "quickly lost whatever claims" the bill's author, Virginia Senator James Mason, had hoped it might have to "community support" in Northern cities such as Harrisburg. [23]

Between September 1850-May 1852, McAllister remanded a total of 18 men and women to slavery—or more than 38% of all fugitives returned during that period. Referencing the table at right, one can see that McAllister's "energetic execution" of the law establishes him as the most prolific fugitive slave commissioner of the 1850s, even though he was only in office until May 1853. The runner-up for this dubious honor is Commissioner John L. Pendery of Cincinnati (the city with the most fugitives remanded), who presided over the famous Margaret Garner case. However, McAllister clearly set the pace for returning fugitives, a vicious rate which was never equalled. It is not hard to see why. McAllister would later speak of being compensated for his "loss" which was indeed very great. He had forsaken his law practice, lost ground within his own church and the community at large. [24] Amidst a Northern public that was growing increasingly resistant to supporting slavery, the Federal government would never again find a man willing to enforce the law as relentlessly as Richard McAllister.

Between September 1850-May 1852, McAllister remanded a total of 18 men and women to slavery—or more than 38% of all fugitives returned during that period. Referencing the table at right, one can see that McAllister's "energetic execution" of the law establishes him as the most prolific fugitive slave commissioner of the 1850s, even though he was only in office until May 1853. The runner-up for this dubious honor is Commissioner John L. Pendery of Cincinnati (the city with the most fugitives remanded), who presided over the famous Margaret Garner case. However, McAllister clearly set the pace for returning fugitives, a vicious rate which was never equalled. It is not hard to see why. McAllister would later speak of being compensated for his "loss" which was indeed very great. He had forsaken his law practice, lost ground within his own church and the community at large. [24] Amidst a Northern public that was growing increasingly resistant to supporting slavery, the Federal government would never again find a man willing to enforce the law as relentlessly as Richard McAllister.

Notes

(Header Image: The Rendition of Anthony Burns, artist's impression, 1899, House Divided Project, [WEB])

1. Richard McAllister to Enoch Louis Lowe, May 5, 1851, Governor’s Papers, Miscellaneous, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, MD.

2.

“Slave Case—Great Excitement,” Harrisburg Pennsylvania Telegraph, August 28, 1850, State Library of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA; “Fugitive Slave Case,” Harrisburg Pennsylvania Telegraph, September 4, 1850, State Library of Pennsylvania; Gerald G. Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 4 (1985): 544-454; Richard Blackett, Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 32-36.

3.

Blackett, Making Freedom, 32-36; Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg,” 544-546.

4.

Charles Rawn Diary, September 30, 1850, The Rawn Journals 1830-1865, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, PA, [WEB].

5.

“Another Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, January 25, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Fugitive Slaves,” Harrisburg Daily American, April 23, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Another Slave Case,” Harrisburg Keystone, August 12, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 158-160.

6.

“Fugitive Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, October 15, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

7.

“Fugitive Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, October 15, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

8.

Quoted in Blackett, Making Freedom, 41-43.

9.

Blackett, Making Freedom, 43-44.

10.

“Murder under the Fugitive Slave Law,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, May 5, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

11.

“Slave Catcher’s Fees,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, May 5, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Fugitive Slave Riot,” Harrisburg Whig State Journal, May 6, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania; “The Murder at Columbia,” Whig State Journal, May 13, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

12.

“The Murder at Columbia,” Whig State Journal, May 13, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

13.

“From Harrisburg,” Philadelphia Pennsylvanian, February 1, 1853, State Library of Pennsylvania.

14.

Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg,” 566-567.

15.

Pennsylvania Telegraph, January 29, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

16.George W. Emerson to Alden Partridge, February 18, 1853, Alden Partridge Records, Correspondence, Norwich University Archives, Northfield, VT, [WEB].

17.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, July 25, 1853, Cameron Family Papers, MG 500, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, PA.

18.

The author of this exhibit is indebted to the faculty of Temple University's Africology Department, where this research was first presented at the Fifteenth Annual Underground Railroad and Black History Conference, on February 14, 2018. Dr. Molefi K. Asante, Dr. Nilgun Anadolu-Okur, Dr. Anthony Waskie and Prof. Timothy Welbeck, Esq. shared their insights on what McAllister's turbulent tenure meant in the larger scheme of the 1850s.

19.

McAllister to Cameron, July 25, 1853, Cameron Family Papers, HSDC.

20.

Quoted in Blackett, Making Freedom, 50-66; Campbell, The Slave Catchers, 158-160.

21.

Harrisburg Morning Herald, June 15, 1854, State Library of Pennsylvania.

22.

Richard McAllister to Stephen Douglas, November 15, 1857, Stephen Douglas Papers, Series I, Box 9, Folder 9, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

23.

Richard Blackett, The Captive's Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 59, 64-65, 459; For "excessive zeal" see “From Harrisburg,” Philadelphia Pennsylvanian, February 1, 1853, State Library of Pennsylvania; For "energetic execution" see McAllister to Douglas, November 15, 1857, Douglas Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

24.

Data for the chart comes from Samuel J. May, The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1861), Campbell, The Slave Catchers, and Steven Lubet, Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial, (Harvard University Press, 2010), eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost).

(Header Image: The Rendition of Anthony Burns, artist's impression, 1899, House Divided Project, [WEB])

1. Richard McAllister to Enoch Louis Lowe, May 5, 1851, Governor’s Papers, Miscellaneous, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, MD.

2.

“Slave Case—Great Excitement,” Harrisburg Pennsylvania Telegraph, August 28, 1850, State Library of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA; “Fugitive Slave Case,” Harrisburg Pennsylvania Telegraph, September 4, 1850, State Library of Pennsylvania; Gerald G. Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 4 (1985): 544-454; Richard Blackett, Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 32-36.

3.

Blackett, Making Freedom, 32-36; Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg,” 544-546.

4.

Charles Rawn Diary, September 30, 1850, The Rawn Journals 1830-1865, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, PA, [WEB].

5.

“Another Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, January 25, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Fugitive Slaves,” Harrisburg Daily American, April 23, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Another Slave Case,” Harrisburg Keystone, August 12, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania; Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 158-160.

6.

“Fugitive Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, October 15, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

7.

“Fugitive Slave Case,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, October 15, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

8.

Quoted in Blackett, Making Freedom, 41-43.

9.

Blackett, Making Freedom, 43-44.

10.

“Murder under the Fugitive Slave Law,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, May 5, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

11.

“Slave Catcher’s Fees,” Pennsylvania Telegraph, May 5, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania; “Fugitive Slave Riot,” Harrisburg Whig State Journal, May 6, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania; “The Murder at Columbia,” Whig State Journal, May 13, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

12.

“The Murder at Columbia,” Whig State Journal, May 13, 1852, State Library of Pennsylvania.

13.

“From Harrisburg,” Philadelphia Pennsylvanian, February 1, 1853, State Library of Pennsylvania.

14.

Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg,” 566-567.

15.

Pennsylvania Telegraph, January 29, 1851, State Library of Pennsylvania.

16.George W. Emerson to Alden Partridge, February 18, 1853, Alden Partridge Records, Correspondence, Norwich University Archives, Northfield, VT, [WEB].

17.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, July 25, 1853, Cameron Family Papers, MG 500, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, PA.

18.

The author of this exhibit is indebted to the faculty of Temple University's Africology Department, where this research was first presented at the Fifteenth Annual Underground Railroad and Black History Conference, on February 14, 2018. Dr. Molefi K. Asante, Dr. Nilgun Anadolu-Okur, Dr. Anthony Waskie and Prof. Timothy Welbeck, Esq. shared their insights on what McAllister's turbulent tenure meant in the larger scheme of the 1850s.

19.

McAllister to Cameron, July 25, 1853, Cameron Family Papers, HSDC.

20.

Quoted in Blackett, Making Freedom, 50-66; Campbell, The Slave Catchers, 158-160.

21.

Harrisburg Morning Herald, June 15, 1854, State Library of Pennsylvania.

22.

Richard McAllister to Stephen Douglas, November 15, 1857, Stephen Douglas Papers, Series I, Box 9, Folder 9, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

23.

Richard Blackett, The Captive's Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 59, 64-65, 459; For "excessive zeal" see “From Harrisburg,” Philadelphia Pennsylvanian, February 1, 1853, State Library of Pennsylvania; For "energetic execution" see McAllister to Douglas, November 15, 1857, Douglas Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

24.

Data for the chart comes from Samuel J. May, The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1861), Campbell, The Slave Catchers, and Steven Lubet, Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial, (Harvard University Press, 2010), eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost).