|

|

Born on April 21, 1819, Richard Beale McAllister was reared in a prominent pro-slavery household just north of Harrisburg. His father, John Carson McAllister, was captain of a local militia company, supervisor of the State Works (Pennsylvania’s canal system) and by the 1830s superintendent of a local railroad. He was also heir apparent to Fort Hunter, the family plantation north of Harrisburg that continued to use slave labor well into the nineteenth century. Family records indicate that John enjoyed harassing and frightening the family’s slaves. One anecdote recounts that John, having overheard “several darkies planning a coon-hunt,” climbed into a tree and imitated a bear to startle the hunting party. [1]

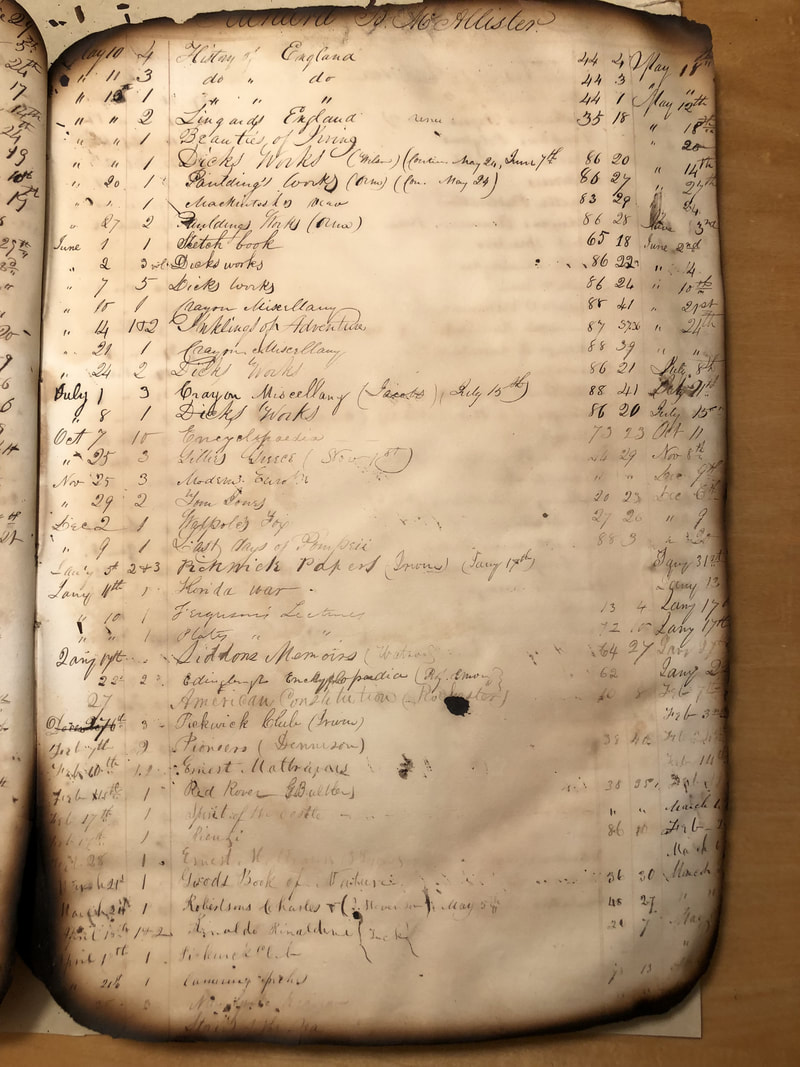

In his late teens, Richard began his studies at Dickinson College. As an active member of the Union Philosophical Society, a literary and debating club, he participated in debates and borrowed frequently from the organization’s library. On May 20, 1837, he checked out the works of James Kirke Paulding, a vocal pro-slavery Democrat from New York, who was then Secretary of the Navy. McAllister may have read the passage where Paulding dismissed African-Americans as “more ignorant than the whites of the poorer classes,” dishonest yet “harmless” and “unthinking[.]”[2] Aside from his apparent inclination for Paulding, McAllister’s thoughts on slavery during his time at Dickinson are more difficult to discern. The only surviving document he created while at Dickinson—his July 1840 commencement address entitled “The eloquence of Nature”—was a mainly philosophic piece, touching on poetry, music and other forms of artistic inspiration. [3] However, McAllister did serve on a committee to select speakers for the Union Philosophical Society, which in 1839 invited former president and then-congressman John Quincy Adams to speak before the society. Adams politely declined, citing his age and other pressing “engagements[.]” [4] Considering Adams’ prominent role in the national anti-slavery movement, his selection by the committee would seem to carry a symbolic meaning. However, McAllister’s feelings on the matter—whether he actively supported the invitation, or was a dissenting voice—remains unknown. After graduating in 1840, McAllister journeyed to Savannah, Georgia, where he studied law with an uncle. He returned to Harrisburg two years later, was admitted to the bar and by 1844 had become a district attorney for Dauphin County. [5] In September 1850, he was appointed as a Fugitive Slave Commissioner for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Click here to read more about McAllister's enforcement of the controversial Fugitive Slave Law. As commissioner, McAllister carried Federal authority to preside and adjudicate on all matters pertaining to fugitive slaves. He quickly made a reputation for himself as a harsh, unrelenting defender of slavery. Slave owners and their agents turned to McAllister as a man they could count on for favorable rulings. His hearings, often held in the pre-dawn hours to preclude the involvement of abolitionist defense counsels, bordered on the extralegal, and soon drew sharp rebukes from the majority of Harrisburg’s residents. In assessing McAllister's tenure, historian Richard Blackett has argued that his purpose was "unmistakably clear: those seeking freedom from slavery must be and would be hunted down and returned at all costs.” While ultimately forced out by the unpopularity of both the Fugitive Slave Law and the way he was enforcing it, McAllister was the most effective commissioner in the entire country while in office, remanding 18 individuals to slavery. During the law's first two years, 38% of those returned to slavery were remanded by McAllister himself. [6] |

After the fugitive slave law

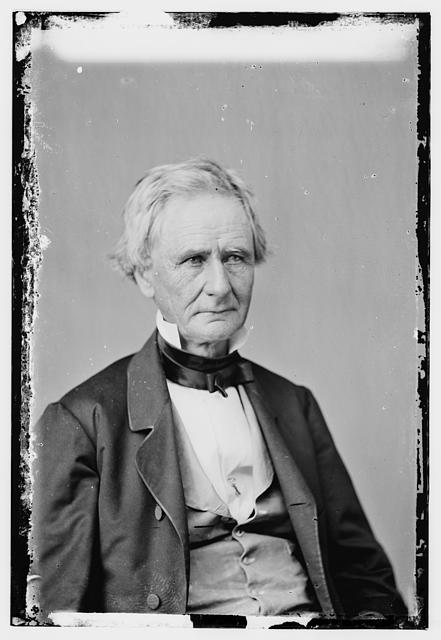

John White Geary, territorial governor of Kansas. (Library of Congress).

John White Geary, territorial governor of Kansas. (Library of Congress).

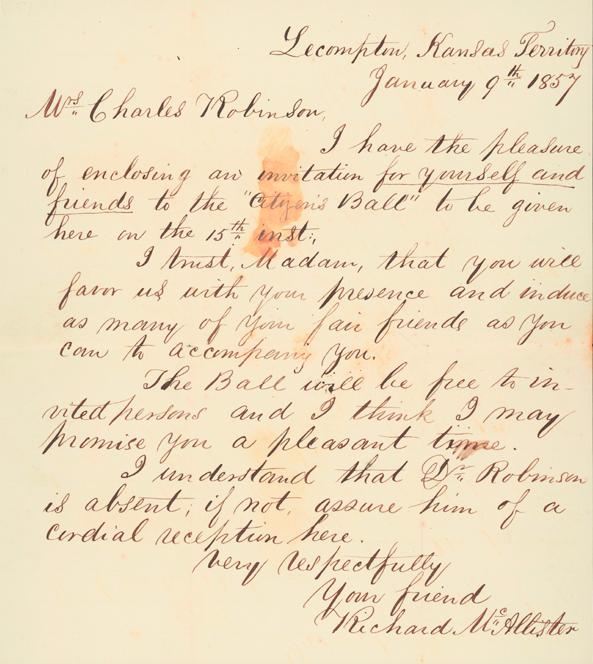

In the aftermath of his resignation as Fugitive Slave Commissioner, McAllister moved west, first to Kansas, where he served as "consulting attorney" to territorial Governor John White Geary. McAllister had seemingly left one arena of turmoil for another, as the troubles over slavery intensified in "Bleeding Kansas." While there, McAllister would "foil" a plot to assassinate Governor Geary by placing himself in-between Geary and a potential assassin. He still saw public office as a lens for personal advancement, eyeing land values in Kansas. "My position here give me the greatest advantage to become acquainted with the best locations and to secure them at the lowest price," he boasted in one letter. [7]

By 1858, he was living in Iowa, where he joined a practice with "one of the oldest and ablest lawyers here[.]" In late 1860 he was appointed postmaster of Keokuk, Iowa by President James Buchanan (Class of 1809). [8] He had only served in that role for several months when the Civil War broke out, and Secretary of War and Harrisburg resident Simon Cameron appointed him a captain of commissary, charged with supplying provisions to Union soldiers. [9]

Cameron had been involved in the Susquehanna Railroad Company with Richard's father, John Carson, and the families maintained relatively close relations. In Iowa, McAllister plied local Republicans to support Cameron for the presidency in 1860, pledging that if Cameron stood "a reasonable prospect of election," he would "throw all party considerations to the wind and go for you with all my might." [10] After Abraham Lincoln was elected, McAllister went so far as to write the president-elect in February 1861, vouching for Cameron's "integrity" and fitness for a cabinet post. When rampant corruption later prompted Cameron's resignation in 1862, McAllister continued in his role as commissary while still maintaining close ties to Cameron. [11]

By 1858, he was living in Iowa, where he joined a practice with "one of the oldest and ablest lawyers here[.]" In late 1860 he was appointed postmaster of Keokuk, Iowa by President James Buchanan (Class of 1809). [8] He had only served in that role for several months when the Civil War broke out, and Secretary of War and Harrisburg resident Simon Cameron appointed him a captain of commissary, charged with supplying provisions to Union soldiers. [9]

Cameron had been involved in the Susquehanna Railroad Company with Richard's father, John Carson, and the families maintained relatively close relations. In Iowa, McAllister plied local Republicans to support Cameron for the presidency in 1860, pledging that if Cameron stood "a reasonable prospect of election," he would "throw all party considerations to the wind and go for you with all my might." [10] After Abraham Lincoln was elected, McAllister went so far as to write the president-elect in February 1861, vouching for Cameron's "integrity" and fitness for a cabinet post. When rampant corruption later prompted Cameron's resignation in 1862, McAllister continued in his role as commissary while still maintaining close ties to Cameron. [11]

the civil war

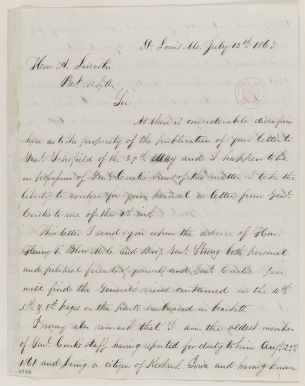

Richard McAllister's letter to President Lincoln, sent in his role as a captain of commissary. (Library of Congress).

Richard McAllister's letter to President Lincoln, sent in his role as a captain of commissary. (Library of Congress).

Wartime service in the western theatre placed McAllister under the commands of Union generals such as Ulysses Grant and Samuel Curtis. Years later, McAllister would assert that he was Grant's "fast friend in the darkest hours of his military history[.]" [12]

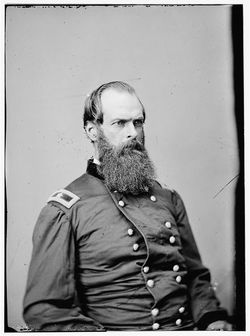

Although far removed from Harrisburg, he remained active in Pennsylvania politics, corresponding with the then-former Secretary of War Cameron and even President Lincoln (whom he had not personally met). In July 1863, he wrote to Lincoln, mentioning "Archibald McAllister... from Penna who is my brother and a very earnest War Democrat[.]" [13]

The former commissioner too emerged as a strong War Democrat, writing to Cameron that he was in favor of “a still more vigorous war policy,” and would accept “[n]othing but unconditional submission on the part of [the] rebels.” He shared these views with his brother, who Richard promised “can afford to be independent as he is the only Democrat who could have carried [the district] and I don't believe he values party ties at the expense of the true interests of his country.” [14]

In 1864, McAllister moved to Washington "to broaden his field of practice[.]" It appears that, having served three years, McAllister was anxious to return to the private sector. In Washington, he apparently realized the social standing he had previously lost in Harrisburg. He would practice law at the U.S. Court of Claims, where individuals submitted bills, expenses or grievances against the Federal government with the hope of compensation. He spent the rest of his life in Washington, until his death in 1887. [15]

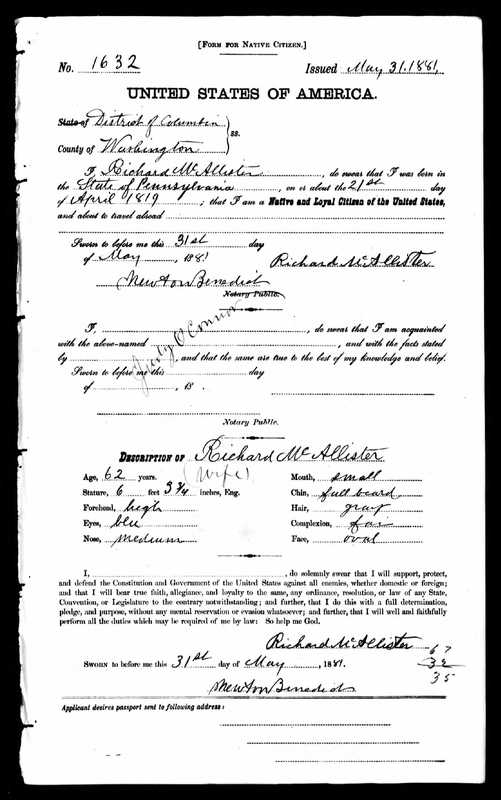

While we lack any known photos of Richard McAllister, this 1881 passport application offers a detailed physical description. Richard reportedly stood 6 feet 3 3/4 inches high, with a high forehead, blue eyes, small mouth and by the end of his life sported a "full beard." (U.S. Passport Applications, Ancestry Database)

Notes

(Header Image: Dickinson College, c. 1845, House Divided Project [WEB]).

1.

Mary Catherine McAllister, Descendants of Archibald McAllister, of West Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County, Pa. 1730-1898, (Harrisburg, PA: Scheffer’s Printing, 1898), 18-19, 45-46, 79; George L. Reed, Alumni Record, Dickinson College, (Carlisle, PA: Dickinson College, 1905), 101; “Dickinson College, Order of Exercises at Commencement,” July 9, 1840, Programs, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

2. Register of the Union Philosophical Society Library, 1837-1842, Oversized Materials, Union Philosophical Society Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College; A.L. Hayes, The Annual Address Delivered before the Belles-Lettres and Union Philosophical Societies of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa., July 19, 1837, (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1837); Sydney G. Fisher, The Annual Address Delivered before the Belles-Lettres and Union Philosophical Societies of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa., July 18, 1838, (Carlisle: George M. Phillips, 1838); J. Hall Beady, The Annual Address, Delivered before the Union Philosophical, and Belles Lettres Societies, of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, July 8, 1840, (Philadelphia: J. Crissy, 1840); James Kirke Paulding, Letters from the South, by a Northern Man, (New York: Harpers & Brothers, 1835), 96-97; Paulding had also written a tract entitled Slavery in the United States, published in 1836, though it is unclear if McAllister read this as part of Paulding’s “works.”

3.

Richard Beale McAllister, “The eloquence of Nature,” Orations 1840, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College; Reed, Alumni Record, 101.

4.

John Quincy Adams to the Union Philosophical Society, November 25, 1839, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, [WEB].

5.

Reed, Alumni Record, 101; Gerald G. Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 4 (1985): 567.

6.

Richard Blackett, Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 41-45, 48, 50-52, 66; Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 158-160.

7.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, October 10, 1856, Cameron Family Papers, MG 500, Historical Society of Dauphin County.

8.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, July 20, 1858, Cameron Family Papers, HSDC; Richard McAllister to Mrs. Charles Robinson, January 9, 1857, Territorial Kansas Online, University of Kansas, [WEB]; John H. Gihon, Geary and Kansas: Governor Geary's Administration in Kansas, with a Complete History of the Territory until June 1857, (Philadelphia: J.H.C. Whiting, 1857), 233-234, [WEB]; David E. Meerse, "No Propriety in the Late Course of the Governor: The Geary-Sherrard Affair Reexamined," Kansas Historical Society, [WEB]; The Twentieth Century Bench and Bar of Pennsylvania, (Chicago: H.C. Cooper, Jr. & Brother & Company, 1903), 2:770, [WEB]; John Nevin (ed.), The Salmon P. Chase Papers: Journals, 1829-1872, (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1993), 1:272; Journal of the Proceedings of the Bishops, Clergy,a nd Laity of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, Assembled in a General Convention, Held in St. Luke’s Church, in the City of Philadelphia, (Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1857), 20; Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, From December 6, 1858, to August 6, 1861, Inclusive, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887), 11:237-244.

9.

Journal of the Executive Proceedings..., 11:490-491.

10.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, July 20, July 30, October 22, 1858, July 1, August 13, 1859, March 9, March 27, 1860, Cameron Family Papers, HSDC.

11.

Richard McAllister to Abraham Lincoln, February 7, 1861, Papers of Abraham Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, IL, [WEB]; See, Richard McAllister to Benjamin Butler, January 24, 1865, quoted in, Jessie Ames Marshall, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, During the Period of the Civil War, (Horwood, MA: Plimpton Press, 1917), 5:516, [WEB].

12.

Richard McAllister to Edwards Pierrepont, November 10, 1875, quoted in, John Y. Simon (ed.), The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 26:316-317.

13.

Richard McAllister to Abraham Lincoln, July 13, 1863, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB]; Simon Cameron to Richard McAllister, November 13, 1864, Papers of Abraham Lincoln, ALPLM, [WEB]; McAllister, Descendants of Archibald McAllister, 79.

14.

Richard McAllister to Simon Cameron, November 12, 1862, Cameron Family Papers, HSDC.

15.

McAllister, Descendants of Archibald McAllister, 79; Twentieth Century Bench and Bar of Pennsylvania, 2:770.