Members of the McAllister family had a lengthy and nuanced relationship with slavery. Learn more about the family's ties to the peculiar institution below.

Slavery at fort hunterFor decades into the early 19th century, slave labor was used at Fort Hunter, the McAllister family's property north of Harrisburg. However in 1828, faced with economic difficulty, Richard and Archibald’s grandfather, Archibald McAllister (1756-1831), sought to “dispose of all my colored people at private sale.” McAllister’s public notice advertised four slaves, one of whom ran away after hearing news of the impending sale. [1]

|

|

Fort Hunter's enslaved population

African-American Cemetery near Fort Hunter. (Photo by Cooper Wingert).

African-American Cemetery near Fort Hunter. (Photo by Cooper Wingert).

Several generations of the Craig (also spelled Crage) family, along with other enslaved families, labored at Fort Hunter well into the 19th Century, negotiating the murky boundaries between freedom and enslavement. While Sall Craig's fate after running away in December 1828 is unknown, members of her family remained, and are buried on a hillside some distance from the McAllister family cemetery. Although in disrepair, several legible tombstones belong to members of the Craig family who had been born into bondage, but had attained freedom (in some degree) by the end of their lives. [2]

archibald mcallister (1813-1883)

"I cast my vote against the corner-stone of the southern confederacy..."

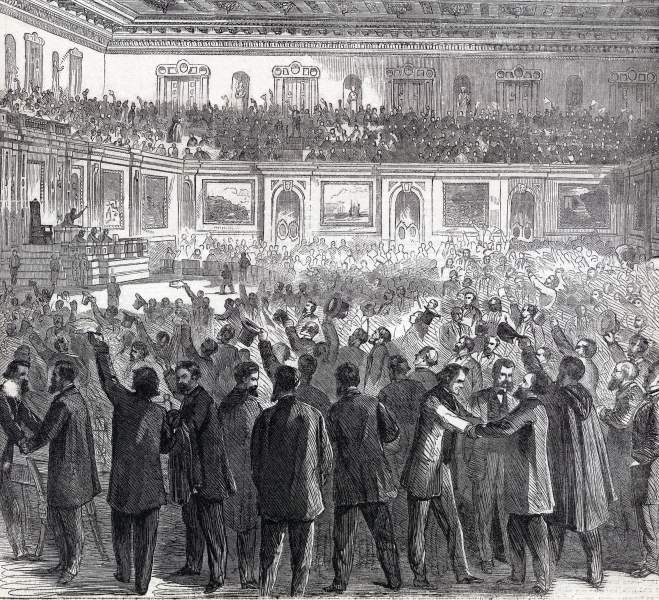

Members of the House celebrate the passage of the 13th Amendment in this Harpers Weekly engraving. (House Divided Project).

Members of the House celebrate the passage of the 13th Amendment in this Harpers Weekly engraving. (House Divided Project).

Despite the McAllister family's many ties to slavery, another family member would later play a decisive role in its demise. Richard’s older brother, Archibald (born at Fort Hunter in 1813), also attended Dickinson College (although he did not graduate) before relocating to Blair County, where he worked as an iron manufacturer.

In 1862, he was elected to Congress as a Democrat, in a district that encompassed several counties in south central Pennsylvania. Serving only one term, McAllister was a lame duck when the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery came up for a second vote in January 1865. Like most Democrats, Archibald had voted against the amendment in 1864—however, come 1865, McAllister was prepared to change his stance.

McAllister’s decision was evident nearly two weeks before the House vote. In mid-January, a bipartisan group of Philadelphians prepared “a handsome dinner to those Democratic Congressmen” willing to cross party lines and vote for the 13th Amendment. A list of invitees compiled on January 20 included McAllister’s name, although not that of Alexander Coffroth, the other Pennsylvania Democrat who ultimately voted in favor of the amendment. [3]

The morning of the vote, Republican floor leaders had mapped out a precise plan. “There was no scramble for the floor,” recalled Edward W. Barber, the House reading clerk. Ohio Congressman James Ashley yielded part of his time to McAllister. “His voice was not strong,” however, prompting McAllister to pass his handwritten speech to the clerk’s desk. There, Barber found himself delivering a “concise” but powerful speech in which the author laid the blame for the war on slavery. [4]

Acknowledging his previous vote against the amendment, McAllister declared his opposition to “secession or dissolution in any shape,” and now argued that the abolition of slavery was the best means to destroy Southern resistance and end the war. The Confederacy, he wrote, “must… be destroyed; and in voting for the present measure I cast my vote against the corner-stone of the southern confederacy, and declare eternal war against the enemies of my country.” [5] Listeners at the time would have recognized McAllister’s allusion to the “corner-stone” of the Confederacy as a response to Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephen’s famous “corner-stone” speech, delivered in early 1861. Stephens had declared that the new government’s “corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” [6]

As Congressman McAllister's note was read, the House chamber filled with applause from his Republican colleagues. They understood the significance of his decision. Later that same day, with McAllister’s vote, the House would ratify the 13th Amendment, reaching the necessary 2/3rds margin with just two votes to spare. [7] Given his family's ties to slavery (especially his brother Richard's earlier infamy as a Fugitive Slave Commissioner), Archibald McAllister was an unlikely figure to play such a momentous role in abolishing slavery. His story is a reminder of the complex ways in which 19th Century American families interacted and associated with slavery.

In 1862, he was elected to Congress as a Democrat, in a district that encompassed several counties in south central Pennsylvania. Serving only one term, McAllister was a lame duck when the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery came up for a second vote in January 1865. Like most Democrats, Archibald had voted against the amendment in 1864—however, come 1865, McAllister was prepared to change his stance.

McAllister’s decision was evident nearly two weeks before the House vote. In mid-January, a bipartisan group of Philadelphians prepared “a handsome dinner to those Democratic Congressmen” willing to cross party lines and vote for the 13th Amendment. A list of invitees compiled on January 20 included McAllister’s name, although not that of Alexander Coffroth, the other Pennsylvania Democrat who ultimately voted in favor of the amendment. [3]

The morning of the vote, Republican floor leaders had mapped out a precise plan. “There was no scramble for the floor,” recalled Edward W. Barber, the House reading clerk. Ohio Congressman James Ashley yielded part of his time to McAllister. “His voice was not strong,” however, prompting McAllister to pass his handwritten speech to the clerk’s desk. There, Barber found himself delivering a “concise” but powerful speech in which the author laid the blame for the war on slavery. [4]

Acknowledging his previous vote against the amendment, McAllister declared his opposition to “secession or dissolution in any shape,” and now argued that the abolition of slavery was the best means to destroy Southern resistance and end the war. The Confederacy, he wrote, “must… be destroyed; and in voting for the present measure I cast my vote against the corner-stone of the southern confederacy, and declare eternal war against the enemies of my country.” [5] Listeners at the time would have recognized McAllister’s allusion to the “corner-stone” of the Confederacy as a response to Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephen’s famous “corner-stone” speech, delivered in early 1861. Stephens had declared that the new government’s “corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” [6]

As Congressman McAllister's note was read, the House chamber filled with applause from his Republican colleagues. They understood the significance of his decision. Later that same day, with McAllister’s vote, the House would ratify the 13th Amendment, reaching the necessary 2/3rds margin with just two votes to spare. [7] Given his family's ties to slavery (especially his brother Richard's earlier infamy as a Fugitive Slave Commissioner), Archibald McAllister was an unlikely figure to play such a momentous role in abolishing slavery. His story is a reminder of the complex ways in which 19th Century American families interacted and associated with slavery.

Notes

(Header Image: Fort Hunter Park, Dauphin County Parks and Recreation Department, photo by Cooper Wingert).

1.

Harrisburg Pennsylvania Reporter and Democratic Herald, December 26, 1828, State Library of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA.

2.

Headstone of Andrew Craig, African-American Cemetery, Fort Hunter, PA.

3.

“Miscellaneous,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, January 20, 1865, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, [WEB]; Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004, reprint), 206.

4.

Edward W. Barber, “The Story of Emancipation: Passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, with Sketches of Michigan Members of the Thirty-eighth Congress,” in Historical Collections made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, (Lansing, MI: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1901), 29:585-586, [WEB]

5.

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess. 523 (1865), [WEB]; “McAllister, Archibald,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, accessed December 6, 2017, [WEB].

6.

Henry Cleveland, Alexander H. Stephens, in Public and Private. With Letters and Speeches, Before, During, and Since the War, (Philadelphia, PA: National Publishing Company, 1866). 721.

7.

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess. 531 (1865), [WEB].

(Header Image: Fort Hunter Park, Dauphin County Parks and Recreation Department, photo by Cooper Wingert).

1.

Harrisburg Pennsylvania Reporter and Democratic Herald, December 26, 1828, State Library of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA.

2.

Headstone of Andrew Craig, African-American Cemetery, Fort Hunter, PA.

3.

“Miscellaneous,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, January 20, 1865, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, [WEB]; Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004, reprint), 206.

4.

Edward W. Barber, “The Story of Emancipation: Passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, with Sketches of Michigan Members of the Thirty-eighth Congress,” in Historical Collections made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, (Lansing, MI: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., 1901), 29:585-586, [WEB]

5.

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess. 523 (1865), [WEB]; “McAllister, Archibald,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, accessed December 6, 2017, [WEB].

6.

Henry Cleveland, Alexander H. Stephens, in Public and Private. With Letters and Speeches, Before, During, and Since the War, (Philadelphia, PA: National Publishing Company, 1866). 721.

7.

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess. 531 (1865), [WEB].